Advantages and Disadvantages of OOP

Varieties of "Classes"

To simplify the learning process, LabVIEW only offered a single type of "class" prior to 2020. However, examining other object-oriented programming languages reveals they often provide many different types of "classes", categorized in various ways.

Access Permissions

Classes can be categorized based on access permissions for their attributes (data) and methods (functions or VIs):

- Public: Accessible both inside and outside the class. Internal access refers to the ability to read and write within the code of methods (functions or VIs) that belong to the same class, while external access encompasses everything else.

- Private: Accessible only within the class and not from the outside.

- Protected: Accessible within the class itself or within any of its subclasses.

- Friend: Some programming languages embrace the concept of "friends", where specific attributes and methods of a class can be accessed by other methods or classes designated as friends.

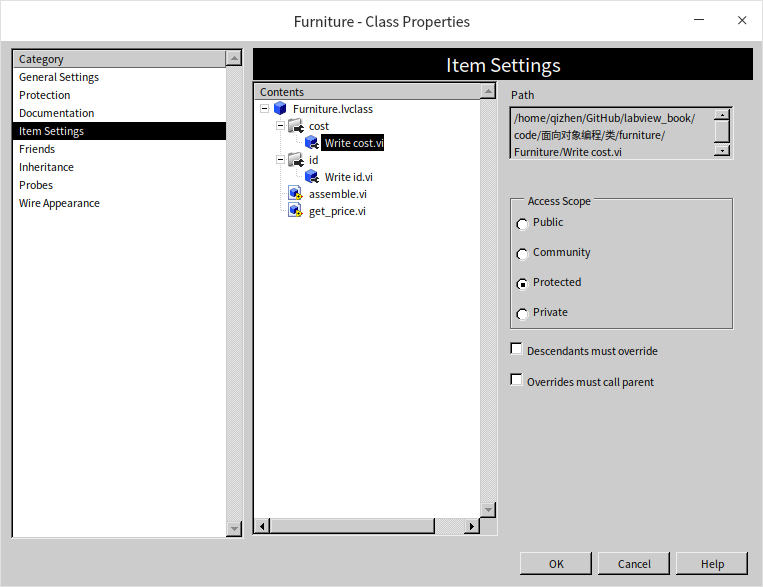

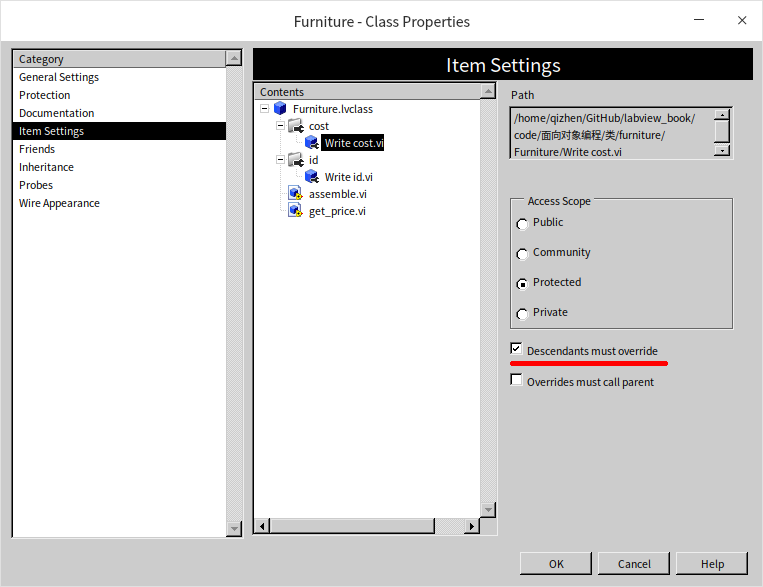

In LabVIEW, class attributes (data) are exclusively private, meaning they can only be read and written by VIs within the same class. However, LabVIEW does support all four types of access permissions for class methods (VIs), which can be adjusted in the class's settings dialog:

It's advisable to set lower-level methods (VIs) to private to prevent their direct utilization by end-users. Before LabVIEW enhanced its private VI protection, I frequently encountered scenarios where tweaking a low-level VI led to user complaints that such changes disrupted their applications because they could no longer use the altered VI as before. These VIs weren't initially meant for user consumption, but since customers have the final say and had been utilizing them, reverting the changes to maintain the VIs' unchanged behavior was often the only recourse. This situation rendered functionality modules incredibly hard to maintain, as any minor detail could affect some clients and was therefore untouchable. By setting lower-level VIs to private, it ensures that users cannot access them, allowing module maintainers to confidently update them. As long as the APIs provided to users remain constant, updates to the underlying structure are feasible without issues.

For instance, in the furniture store example from the previous section, the data access methods in the Furniture class were meant solely for use by methods in descendant classes, so they should be set to "Protected" permission.

Some languages allow setting access permissions for the class itself, as private or public. This facilitates modular hierarchy: an application can be segmented into several large modules, each further divisible into smaller modules. These smaller modules can be defined as private or shared across different large modules. While LabVIEW classes cannot nest, LabVIEW libraries can be nested, and it's feasible to divide a large project into multiple libraries, each containing several classes. In this scenario, a class, as a library member, can also be designated as private or public.

Instantiation Requirements for Classes

Classes can be categorized based on their need for instantiation before their attributes and methods can be accessed:

- Static: Static attributes and methods do not require the class to be instantiated for access.

- Dynamic: Dynamic attributes and methods require an instance of the class to be accessed.

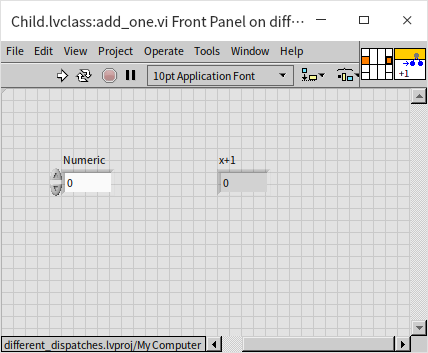

It's important to distinguish that the "dynamically dispatched template" and "statically dispatched template" in LabVIEW are entirely different from the conventional dynamic and static concepts discussed in other programming languages. By the standard definitions used in most languages, the attributes and methods we've shown in LabVIEW classes are predominantly dynamic: the VIs within the class all feature a "class" input control, and this input is mandatory. Meaning, these VIs cannot be invoked without providing an instance of the class. LabVIEW classes can also contain "static methods" by including a regular VI that lacks a class input control. As illustrated below, although this VI is located within a class, it lacks class input, allowing it to be directly called from anywhere.

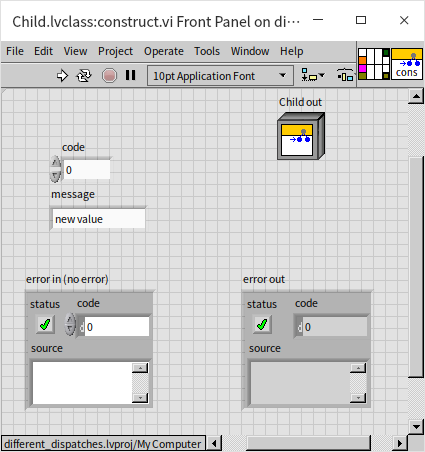

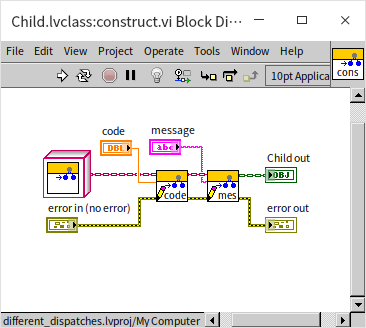

This approach effectively utilizes the class's encapsulation feature, grouping it with related VIs within the same class. Some VIs, particularly constructor VIs that don't have class input but can create and initialize a class instance, are ideal for class encapsulation. These VIs are capable of setting initial object data, opening necessary files, instruments, and establishing network connections, etc. Below are examples of a constructor VI:

Except for this segment, when discussing "static" and "dynamic" within the context of classes, this book adheres to LabVIEW's definitions of static and dynamic, rather than the broader programming context of whether instantiation is required for class access.

Whether Subclass Overriding is Required or Mandatory

Classes can be categorized based on their need for methods to be overridden by subclasses:

- Ordinary Functions: In many languages, ordinary functions, similar to virtual functions discussed below, can be inherited and overridden by subclasses. They differ from virtual functions in that they lack polymorphism (dynamic binding). LabVIEW does not have an equivalent VI type for ordinary functions.

- Virtual Functions: These correspond to LabVIEW's "dynamically dispatched template" VIs, indicating that the function or VI can be inherited, overridden by subclasses, and exhibit polymorphism.

- Final Functions: These functions cannot be overridden by subclass functions. In LabVIEW, they correspond to "statically dispatched template" VIs, which cannot be rewritten by VIs in subclasses.

- Abstract Functions: Also known as pure virtual functions, these virtual functions are typically defined by their name and input/output parameters in the base class without any implementation. Abstract functions must be overridden in subclasses with actual code before they can be invoked. In LabVIEW, a method VI can be set to require overriding in descendant classes, making such VIs effectively abstract or pure virtual:

Like functions, classes can be either ordinary or abstract, and some languages feature final classes.

- Abstract Classes: These classes cannot be instantiated and are meant solely for inheritance by subclasses.

- Final Classes: These classes cannot be inherited.

What purpose do non-instantiable classes serve? In the furniture store example from the previous section, the store sells only tables and chairs. We defined a "Furniture" class as a parent class with two subclasses: "Table" and "Chair". This Furniture class should be an abstract class since the store does not sell any furniture types beyond tables and chairs. Setting the Furniture class as abstract forces programmers to create furniture objects only from the Table or Chair classes, preventing the creation of furniture that doesn't conform to the expected types.

Setting the Table and Chair classes as final classes would not be appropriate because furniture can be further divided into many categories, such as recliners and benches, which could be derived from the Chair class. The use of final functions and classes is typically motivated by security concerns. For instance, if we developed a class for password verification, making the class final prevents someone from overriding the password verification logic in a subclass and passing it to the caller.

LabVIEW lacks a specific definition for abstract classes, but in the next section, we introduce a very similar concept: "interface". Interfaces can be used to achieve the functionality of abstract classes.

Multiple Inheritance

The Challenges of Multiple Inheritance

LabVIEW classes do not support multiple inheritances; a class can have only one parent class but can have numerous subclasses. Despite this, real-world scenarios frequently arise where multiple inheritances would be desirable. Consider a furniture store scenario that sells only tables and chairs but has a peculiar piece of furniture that functions both as a table and a chair:

This combo table-chair possesses both the attributes and methods of tables and chairs, intuitively suggesting it should inherit from two parent classes: "Table" and "Chair". Ideally, it would inherit attributes and methods from both, but limitations to single inheritance, such as inheriting only from the Chair class, mean that table attributes and methods would need to be re-implemented from scratch, which is inefficient. Beyond inefficiency lies a bigger problem: if a program designed to process tables can only accept table objects, it wouldn't be able to process the combo piece since it inherits from the Chair class, despite being a type of table too.

Some programming languages, like C++, allow multiple inheritances, but this capability introduces several significant issues, such as conflicts in property and method calls. With multiple inheritance, a "Combo Table-Chair" class could inherit from both Table and Chair classes. If both parent classes have methods with the same name, which one should the Combo Table-Chair class inherit?

- In some cases, it may be necessary to retain methods of the same name from both parents. For example, both tables and chairs might have a "Return Weight Capacity" method, but the table and chair parts of the combo furniture might have different capacities, requiring both parents' methods to be retained.

- Other times, it might be appropriate to keep only one version of the method with the same name, such as a "Return Price" method. The combo furniture piece can't logically return two different prices.

- A more complicated situation arises when a program designed to process all furniture, taking "Furniture" as its input type, receives a combo table-chair instance. When the program calls the "Return Weight Capacity" method, should it execute the method inherited from the Table class, the Chair class, or the original method from the "Furniture" class?

Programming languages do define rules for these scenarios. The challenge is that programmers may struggle with understanding and implementing these rules correctly, leading to code that yields baffling results. Thus, the issues stemming from multiple inheritances often outweigh its benefits. A common recommendation for C++ programming is to avoid multiple inheritances. Reflecting on C++'s lessons, many newer mainstream programming languages have outright removed the feature for class multiple inheritances. So, how can we accommodate a combo table-chair in a system that requires it to be recognized by both table and chair processing programs without multiple inheritances? The solution lies in using "interfaces".

Interfaces

Interfaces can be likened to abstract classes composed exclusively of abstract functions. They allow for multiple inheritances without causing confusion because they only offer method definitions without actual implementations. It's clear that methods within an interface won't be directly called by a program since there's no implementing code. When a class inherits from a parent class, it's to leverage the parent's implemented methods. Conversely, inheriting an interface compels the class to implement all the methods the interface demands. Naturally, a class can inherit from multiple interfaces, ensuring it supports every method defined across these interfaces. For instance, a hybrid table-chair inheriting from both "Table" and "Chair" interfaces signifies it possesses functionalities of both, making it compatible with programs processing either tables or chairs.

While interfaces address the challenge of enabling an object to support functionalities of various types—thereby making it compatible with diverse programs handling different data types—they don't tackle the issue of minimizing code redundancy effectively. That's because many methods, already defined elsewhere, can't be inherited. Various programming languages have introduced different strategies for more efficient code reuse. PHP, for example, introduced Traits—a block of code encapsulated in a manner similar to a class. Classes can utilize a defined Trait, like TableTraits, which encapsulates methods common to tables, such as the put_tablecloth method. A class named DeskClass utilizing TableTraits inherits all its encapsulated methods. A Trait can be utilized by multiple classes, and a class can employ multiple Traits. Therefore, another class named DiningTableClass that uses TableTraits also inherits the put_tablecloth method.

Distinct from class inheritance, methods from Traits are directly incorporated into the class, making them indistinguishable during execution from methods natively implemented in the class. This approach solves the ambiguity of method implementation that arises with multiple inheritances, as seen with DeskClass:put_tablecloth and DiningTableClass:put_tablecloth methods.

Java took a different approach to this issue by allowing interfaces to provide default method implementations. If a class using the interface doesn't override a method, its objects default to using the method as implemented in the interface. Given that interface methods can now have implementations, and considering the possibility of multiple inheritances, restrictions are necessary to avoid reintroducing all the problems associated with class multiple inheritances. Java imposes a restriction for using default implementations in classes: if a class implements several different interfaces with identically named methods, and these interfaces offer default implementations, the class must override this method. This ensures any program using the class's objects knows it's invoking the method as overridden in the class, not any interface-implemented method. This clarity prevents the confusion about call relationships that multiple inheritances often bring.

Object-Oriented Programming and Data Flow in LabVIEW

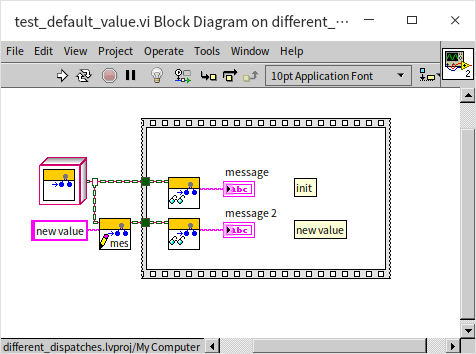

Let's consider whether LabVIEW class objects are passed by value or by reference in programs. A simple experiment can shed light on this question:

If we pass an object along two branches and modify its data on one branch, the data on the other branch remains unaffected. Thus, similar to most data types in LabVIEW, class objects are passed by value.

LabVIEW operates on a dataflow-driven programming model. Data travels along wires, each node receiving data through its input, processing it, and then passing the result through its output. Aligning with the data flow concept, LabVIEW functions or VIs predominantly utilize pass-by-value: as if data flows entirely along the wire into the node, and whenever there's a fork, a duplicate of the data is created. This ensures two identical but independent data pieces continue along different paths.

To preserve this dataflow-driven methodology users are accustomed to, LabVIEW class objects also navigate between nodes by value, which is distinct from the approach of many other programming languages where objects are typically passed by reference.

Pass-by-value and pass-by-reference each have their unique advantages. LabVIEW's unique selection of pass-by-value is because the benefits of value passing are more pronounced within LabVIEW's context.

The primary advantage of pass-by-reference is its efficiency, as objects often consist of large amounts of data. In languages like C, where function parameters are passed by stacking, large data volumes can make stack operations costly. Meanwhile, a reference typically occupies only 4 or 8 bytes, making it far less costly than passing the data directly. LabVIEW does not use stack pushing when passing parameters to subVIs. With well-designed programs allowing for cache reuse, where subVI parameters directly utilize the source data's memory, the efficiency of parameter passing is significantly improved. Thus, in LabVIEW, pass-by-value doesn't detrimentally affect efficiency as it might in languages like C.

In multithreaded programs, passing by reference means different threads can access the same data block, making concurrent read-write operations risky and potentially leading to unpredictable results. Critical sections, semaphores, and other mechanisms are often employed to prevent race conditions. This scenario is manageable for programmers accustomed to multithreading in languages like C++. They're generally aware of the risks of race conditions and take measures to avoid errors.

A substantial portion of LabVIEW's user base, however, are not computer science experts. To facilitate the use of multithreading more straightforwardly, LabVIEW employs an automatic multithreading mechanism. Developers don't need to explicitly create new threads; any two code segments without a logical sequence dependency may automatically execute in parallel threads. In this environment, passing by reference becomes perilous, as programmers might be unaware of their program's multithreaded nature, inadvertently writing code that leads to race conditions.

Pass-by-value resolves this issue. It means that when necessary, data is duplicated at each fork, creating equal but independent copies for each potentially concurrent execution path. This ensures data remains isolated, preventing unintentional race conditions. If a program needs to process the same object across different threads, developers can consciously use LabVIEW's pass-by-reference mechanisms, understanding the associated risks and implementing thread safety precautions.

The Influence of Object-Oriented Principles on LabVIEW Programming

In the current landscape of LabVIEW program development, the process typically begins with designing and implementing the top-level VI, often the main interface of the program. From this point, the development strategy generally follows a top-down approach. This methodology tends to result in most program modules lacking reusability, necessitating their redevelopment for each new project. Only a handful of foundational modules at the very bottom might be versatile enough for reuse.

As program sizes expand, the overlap between different projects increases, leading to more components that could potentially be reused. Consequently, the efficient management, maintenance, and reuse of these modules have become crucial factors in software development productivity. Programmers are increasingly concentrating their efforts on the thoughtful design and creation of these modules.

Object-oriented programming emerged in response to these challenges, offering a way to encapsulate program functionalities into modules to enhance their universality and security. It supports the inheritance of module features, streamlining the development of new modules. Modules can be developed and tested in parallel, making collaborative work more manageable. These advantages significantly elevate the efficiency of developing extensive LabVIEW programs. As a result, LabVIEW applications built on a foundation of various modules are poised for a substantial leap forward in scale.

Efficiency Issues Stemming from LVClass Memory Loading

A LabVIEW user once expressed frustration over his program taking several minutes to open each time, a situation he found increasingly intolerable. Analysis of his project pinpointed the cause of the efficiency bottleneck: the extensive use of LvClass. His project included hundreds of classes (LvClass), and the proliferation of LvClass was identified as a primary factor in the reduced efficiency.

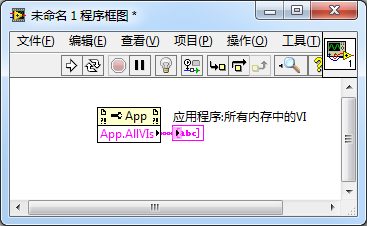

LabVIEW features a property node capable of displaying all VIs currently loaded into memory. This tool allows users to determine precisely which VIs are loaded after a program is opened:

If a VI doesn't belong to any LvClass and includes no subVIs, opening this VI (even if it's part of an lvlib) results in only that specific VI being loaded into memory. However, opening a VI within an LvClass triggers the loading of not just that VI but all other VIs within the same class into memory. Furthermore, if this class is a descendant of a parent or ancestor class, then all VIs within those parent and ancestor classes are also loaded into memory, compounding the efficiency issue.

Summary

When a VI is loaded into memory, the following occurs:

- All its subVIs are also loaded into memory.

- Every VI within its class gets loaded into memory.

- Every VI within its parent class gets loaded into memory.

- These rules apply recursively.

For example, if a main VI, A.vi, is loaded, its subVI, B.vi, will be loaded too, along with C.vi that belongs to the same class as B. If C contains a subVI, D.vi, from class E.lvclass, and E's parent class is F.lvclass with a method VI G.vi, then G.vi will also be loaded into memory, even if it has no direct relevance to A.vi. This program might not seem extensive at first glance, but starting it up could involve loading many unrelated VIs into memory, potentially delaying the process by several minutes.

Given LvClass's characteristics, careful design is crucial. Keep in mind:

- For mere VI encapsulation, opt for lvlib instead of lvclass. Lvlib encapsulates methods (VIs), whereas lvclass can encapsulate both methods and object attributes (data used by the module).

- Ensure that VIs within a class are highly cohesive, working together to accomplish a basic function that cannot be further divided. If an application is likely to use only a few VIs from a class, then employing a class may not be necessary.

- Simplify inheritance structures as much as possible and avoid unnecessary inheritance. Without support for interfaces in LabVIEW, creating purely virtual classes intended as interfaces should be avoided.

- Avoid nested calls within classes. For example, refrain from calling a VI from one class within a VI of another class.

- Exercise caution when using class polymorphism. While polymorphism allows applications to select an appropriate method based on an object's type at runtime, some choices should be determined at compile-time and might not be suitable for polymorphism.

Specific Examples:

- A module for reading and writing INI files suits class design, with each INI file represented by a class instance. It involves rich data (file content) and a limited number of methods (open, read entries, write entries, save, and close), typically used together in applications.

- Complex instrument driver programs are ill-suited to class design due to the vast number of functionalities provided. For instance, an oscilloscope may have various trigger modes, but an application usually requires only one.

- A module for generating user reports in a testing program, where users can choose different report types at runtime, can be well-designed using lvclass. Significant code reuse across methods for generating different report types makes it practical to design a base class.

- A testing program supporting various instrument models should not use lvclass for selecting instrument drivers. Although different users may employ different hardware, a specific user's hardware setup is fixed. The selection of instruments should be determined upon program release, not each time the program is run.

Handling LVClass Memory Loading and Type Conversion Issues

Let's conduct an experiment to determine if we can convert an LVClass object into an XML format for file saving and then revert the data back to the corresponding LVClass object.

Initially, we assign some data to an object of a subclass. Then, we treat it as a parent class type, flatten it into XML text, and save it:

After closing and reopening LabVIEW, we write a program to reverse the process, converting the XML data back into the parent class type data:

We encounter an error from the Unflatten From XML function, resulting in an output of an empty data set.

This error occurs because, although the object's type changes to that of the parent class during conversion, its data remains that of the subclass. Consequently, when converting to XML format, the XML format still captures the subclass data.

In the reverse process, when Unflatten From XML receives subclass data but discovers no subclass type information in memory, it fails to know how to convert the data, hence the error.

If we slightly modify the program to directly convert XML data back into subclass data, it proceeds without errors:

Indeed, subclass data can always be represented using the parent class. Therefore, this XML data can also be directly converted back to the parent class type, provided the subclass type has already been loaded into memory. Merely placing an object of the subclass in the program automatically loads the subclass into memory. A program like the following would function correctly:

From this experiment, we observe:

- If the XML content is of a specific LVClass type, converting this data back into the corresponding LVClass object is feasible only if the LVClass is already loaded into memory. Otherwise, LabVIEW is unable to perform the conversion.

- As mentioned previously, loading a subclass into memory also loads all its parent classes. However, the converse is not applicable. A class has a definite hierarchy of parent classes, and the parents' addresses are cataloged within the subclass. But a parent class cannot anticipate its potential subclasses since anyone could derive various subclasses from it. Therefore, when a parent class is loaded into memory, it cannot simultaneously load all its subclasses.