OOP Design Methods and Principles

In the previous discussions on object-oriented programming (OOP), we mainly considered the implementation perspective: given the classes we know are needed, how do we go about coding them? Moving forward, we'll shift our perspective to design considerations: for a given problem, what classes should we design, and how should they relate to one another?

Object-oriented programming is fundamentally intended for large-scale software development. For smaller programs, many of its methodologies might seem like overkill. This is because OOP takes into consideration the ease of future upgrades and extension of functionalities during the design phase—concerns that are often unnecessary for smaller, disposable programs. For small programs likely to be used once and discarded, worrying about maintenance and upgrades is irrelevant. Even if new needs arise, modifying or even rewriting small programs is not a big deal. Thus, spending excessive time on object-oriented design for a small project does not make sense.

However, the scenario changes dramatically with large-scale software. Such software systems entail significant development costs and are not easily discarded. When faced with new requirements, it's generally impractical to develop another large-scale software system from scratch. More logically, the existing system would be patched and extended. Hence, when designing large programs, one should already anticipate future expansions. For example, when designing a pet store system, it should be considered that new animal categories might need to be added, potentially with different properties and methods. When designing a student report system, the potential need to expand report content, formats, and delivery methods should be anticipated. Similarly, when designing a testing system, possible future expansions, such as new test items, types of products, or testing instruments, should also be considered.

Neglecting to prepare for future expansions during the design phase can make extending the system later on extremely difficult. Adopting OOP aims to build a system that is both flexible and stable: flexibility is shown by the ability to add new features anytime, while stability comes from not needing to change existing classes. So, how do we add new functionalities without modifying existing code?

We've already extensively discussed the three major characteristics of OOP in previous sections: encapsulation, inheritance, and polymorphism. These characteristics remain the most important considerations in program design, meaning when designing classes, we need to think about which properties and methods a class should have, and whether it can inherit properties and methods from other classes. Since these characteristics have been thoroughly explored in earlier chapters, we will focus here on other common design methods and techniques, such as class dependencies and composition.

Additionally, computer scientist Robert C. Martin introduced several principles for object-oriented program design in 2000. These principles have been refined and summarized into five guidelines known as the SOLID principles, essential for object-oriented program design:

- S - Single Responsibility Principle (SRP)

- O - Open/Closed Principle (OCP)

- L - Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP)

- I - Interface Segregation Principle (ISP)

- D - Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP)

These principles are crucial, and we will also introduce them in the following text. It’s worth noting that the order of these principles forms the acronym SOLID, but we will start with the foundational principles first for clarity.

Abstraction

The concept of abstraction, which we've touched upon multiple times, involves extracting common features from a group of entities to form a more generalized concept or model. For example, identifying common characteristics across various dogs to abstract them into a "Dog" class is a classic case of data abstraction. In program design, we go a step further by extracting common traits from various classes to create a more general interface. This interface defines shared properties and behaviors without delving into the specifics of implementation. Abstraction simplifies the design of a system by concealing unnecessary details and highlighting key features. By outlining common properties and behaviors, it prevents the repetition of the same code in multiple areas. Building on an abstract foundation makes it easier to expand or modify the system, creating a variety of specific subclasses.

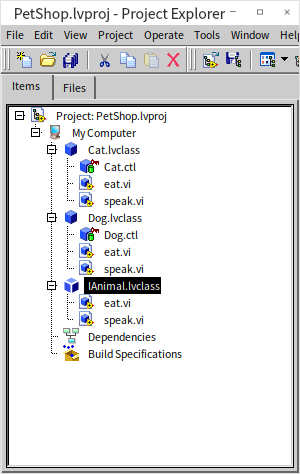

Consider designing a pet store system that includes a variety of animals like cats and dogs. Despite their diverse traits, these animals share several similarities: each has a name, requires food, and can produce sounds. These shared characteristics can be abstracted into an "Animal" interface:

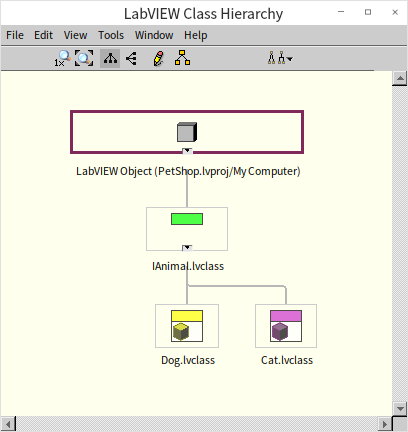

In this IAnimal interface, we specify common methods such as set_name, eat, and speak. However, we do not provide detailed implementations for these methods. After this abstraction process, we can define concrete animal classes based on this abstract Animal interface. The final inheritance structure of the project looks like this:

Each specific animal class implements the IAnimal interface, providing a concrete implementation for the speak method. This design approach allows for the easy addition of more animal types to the system without starting from scratch to define common attributes and behaviors every time. This demonstrates the effectiveness of abstraction.

Similarly, when designing a student report system, it's important to identify any commonalities (such as being printable or mailable) among different types of reports that can be extracted. Likewise, in a testing system design, considering the shared aspects that can be abstracted among different instruments, as well as among various testing items, is crucial.

The Liskov Substitution Principle

The Liskov Substitution Principle mandates that subtypes must be interchangeable with their base types without causing errors.

This means if we have an instance of a parent class, we should be able to swap it with an instance of any of its subclasses without breaking the application. Ignoring the Liskov Substitution Principle undermines our confidence in substituting a subclass wherever a parent class is expected, diminishing code reusability. Utilizing such subclasses carelessly within a program, while ensuring error-free operation, incurs increased testing and maintenance costs.

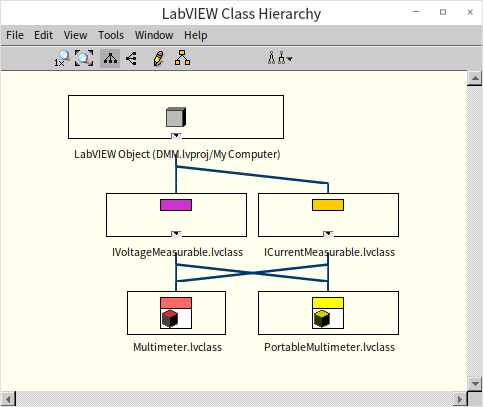

Consider a scenario in a testing program involving two types of multimeters: a standard one, represented by a class named Multimeter, and a portable multimeter, distinguished as a special type but sharing significant functionality with the standard multimeter, hence defined as a subclass named PortableMultimeter.

In everyday logic, this classification seems straightforward. However, within the context of a programming project, defining PortableMultimeter as a subclass of Multimeter might inadvertently lead to its misuse as a substitute for Multimeter. The catch is that the portable multimeter might not completely fulfill the common multimeter's role—for example, it might offer lower measurement accuracy, potentially introducing errors into the program. Thus, making PortableMultimeter a subclass of Multimeter contravenes the Liskov Substitution Principle.

To comply with the Liskov Substitution Principle, we might rethink these classes, ensuring PortableMultimeter is not a Multimeter subclass but rather, both are subclasses under more generalized interfaces. For instance, we could establish interfaces for voltage and current measurements, named IVoltageMeasurable and ICurrentMeasurable, respectively, with the inheritance structure shown below:

Consequently, both PortableMultimeter and Multimeter implement the IVoltageMeasurable interface. This removes the direct parent-child linkage, rendering them as two parallel and independent classes. This approach eliminates concerns about misusing a PortableMultimeter as a Multimeter, thus adhering to the Liskov Substitution Principle. This example illustrates that class design in object-oriented programming is fundamentally aimed at facilitating software development. The focus when crafting classes and their interrelations should be on fostering logical coherence within the program rather than mirroring real-world entity relationships.

Dependency Relationships

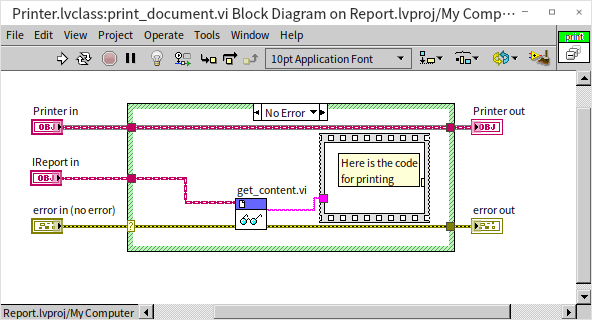

Dependency relationships are a form of loose connection that indicates one class utilizes objects from another class within its methods. Beyond inheritance, classes can relate to each other in various ways, with dependency being among the most common relationships in project development. If Class A's methods employ objects from Class B, Class A is said to be dependent on Class B. Unlike the forthcoming discussions on composition and aggregation, dependency does not imply a strong association with the lifecycle of the involved classes. For instance, consider a scenario involving a Printer class capable of printing various documents and an IReport interface representing these documents. Here, the Printer class is dependent on the IReport interface because it requires an instance of IReport to execute its printing tasks.

Below is a simplified version of the print_document.vi found within the Printer class:

In this illustration, print_document.vi accepts an object from the IReport interface as an input to print its content. This setup shows that the Printer class depends on IReport, yet this dependency does not suggest that Printer owns IReport or that the lifespan of IReport is tied to Printer. It merely indicates that the Printer class makes use of the IReport interface for some of its functionalities.

Such a relationship is transient, existing only for the duration of the method call.

Dependency Inversion Principle

The Dependency Inversion Principle dictates that classes should not depend on other classes but rather on interfaces.

Traditionally in procedural programming, it's typical for higher-level modules to depend on lower-level ones. It seems logical to think that since abstractions are derived from concrete entities, abstractions should depend on the concrete. However, this principle is called "inversion" because it champions the exact opposite: "Abstractions should not depend upon details; rather, details should depend upon abstractions". This means higher-level classes shouldn't rely on lower-level classes; both should depend on interfaces instead.

While this principle is the last in the SOLID sequence, it actually underpins the other principles and design approaches. At its core, the Dependency Inversion Principle aims to decouple classes by insisting on abstraction rather than direct interaction. This lowers the coupling between classes, ensuring that changes in one class minimally impact others, hence simplifying maintenance and facilitating extensions.

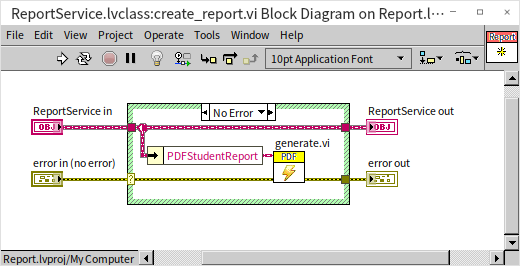

To elucidate this principle, let's look at a report generation example: Imagine we have a ReportService class that directly relies on a specific PDFStudentReport class for generating PDF reports. Here is the block diagram for the create_report.vi within the ReportService class:

In this scenario, create_report.vi directly retrieves an instance of the PDFStudentReport class from the data and invokes its generate.vi to produce a PDF report.

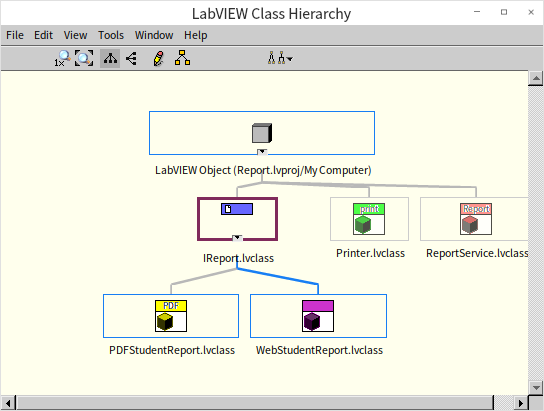

The flaw in this setup is the ReportService's direct dependency on PDFStudentReport. Should the requirement evolve, necessitating web format reports, for instance, we'd be compelled to alter the ReportService class. By adhering to the Dependency Inversion Principle, we can accommodate new report formats without amending the ReportService. This can be achieved by introducing an abstract IReport interface, with PDFStudentReport and other report types (like WebStudentReport) implementing this interface. ReportService should then depend on this abstract IReport interface, not any specific class. The modified class relationships are illustrated below:

Now, ReportService class is designed to accept an IReport interface instance through its constructor. This approach allows us to seamlessly switch report types by simply supplying a different IReport implementation, negating the need to tweak the ReportService class.

The Single Responsibility Principle

The Single Responsibility Principle (SRP) succinctly states that a class should only have one reason to change.

What exactly constitutes "one reason"? Put more specifically, a class should be tasked with a single area of functionality, indicating that only when a specific aspect of the software's requirements changes should the class need to be updated. For instance, consider a program designed to manage student information, which involves fetching student data from a database and formatting it for print. There are various strategies for structuring the classes within such a program. One approach could involve a Student class with two primary responsibilities: retrieving information from the database to populate its attributes and processing these attributes to generate a report.

The problem with this design lies in its response to change. Whether changes are needed in how student data is handled or in the requirements for the report format, adjustments would need to be made to the same class. A design that adheres to the Single Responsibility Principle would segregate these responsibilities into distinct classes. For example, a StudentReport class could exclusively focus on report generation, while a separate Student class would deal with data management. With this refined approach, changes to data management practices could be implemented independently of modifications to report generation, and vice versa.

Why adhere to the Single Responsibility Principle?

First, large projects often involve collaboration among multiple individuals or teams, each possibly responsible for different aspects of the project. Merging disparate functionalities within a single class can lead to conflicts when modifications are necessary. Furthermore, adhering to the SRP can simplify code versioning. Each functionality, represented by a specific class or file, becomes easier to track; any updates to a file immediately signal changes to its associated functionality. Similarly, when adjustments to a specific function are required, the relevant class or file can be identified and modified directly.

Interface Segregation Principle Simplified

The Interface Segregation Principle (ISP) insists that a class shouldn't be compelled to implement interfaces it doesn't use. Overly broad interfaces force classes to implement functionalities they don't need. This principle advocates for splitting large interfaces into smaller, more specific ones so that classes can implement only the functionalities relevant to them.

Take, for instance, our student report system. Initially, we had an IStudentReport interface defining functionalities for generating, emailing, and printing reports. The PDFStudentReport class, handling PDF reports, had to implement all these functions, even printing, which it needed.

The problem arose with a new requirement for web format reports that needed emailing but not printing. Implementing the IStudentReport forced our WebStudentReport class to include a print function it never used. This clearly violates the ISP.

To align with ISP, we divided IStudentReport into distinct interfaces: IReportGeneratable for report generation, IReportEmailable for emailing, and IReportPrintable for printing. Consequently, PDFStudentReport implements all three, aligning with its capabilities, whereas WebStudentReport only needs to implement IReportGeneratable and IReportEmailable, excluding the unnecessary printing functionality.

This approach adheres to the ISP by ensuring classes are not burdened with unnecessary implementations. It encourages designing focused, single-purpose interfaces and classes rather than broad, all-encompassing ones. For example, rather than a catch-all multimeter interface, it's more efficient to have separate interfaces for measuring DC voltage, AC voltage, DC current, etc. This method simplifies class design, making systems more flexible and maintainable.

Association

Association outlines the links between objects in one class to objects in another. These connections can be unilateral or reciprocal and vary in durability, ranging from temporary to permanent. When conceptualizing an association, focus on two main aspects: the directionality, indicating whether the relationship between two classes is one-way or two-way, and the multiplicity, indicating whether an object is linked to one or several objects of another class.

For instance, consider a school system with Teacher and Student classes. The relationship between these two classes' objects represents an "association" relationship: a teacher can teach multiple students, and a student can be taught by multiple teachers.

................

In the example provided, the relationship between Teacher and Student is bidirectional and clearly defined in terms of multiplicity; a teacher can have multiple students, and a student can have multiple teachers. In the Teacher class, the associated Student objects are stored within a list. Utilizing the add_student() method establishes this bidirectional connection. Such a design allows for the easy querying and manipulation of the associations between objects, such as identifying all of a teacher's students or all of a student's teachers.

Composition

Composition denotes a "whole-part" relationship where an object comprises one or more instances of another object. Composition enables the creation of more complex, feature-rich objects based on existing ones without the need for inheritance. Offering greater flexibility than inheritance, composition allows for behavior changes in the whole by merely adjusting the components. It aids in system decoupling, with each part being independently developable and testable, simplifying the management and comprehension of complex systems.

Consider simulating a dog with a Dog class, where a dog consists of a head, body, four legs, and a tail, with legs featuring multiple joints like hips and knees. In this scenario, the relationship between "dog" and "head" should be one of composition, not inheritance; "dog" comprises "head", "body", "tail", etc.

........................

Initially, we define classes for body parts such as joints, legs, and tail.

........................

Subsequently, we create the Dog class, where each Dog object incorporates four instances of the Leg interface and one instance of the Tail interface.

........................

Now, to make the dog walk, we simply invoke the walk method. When expressing happiness, the express_happiness method is called.

........................

Through composition, we've endowed the Dog class with a variety of functionalities while keeping the code organized and maintainable. Should there be a need to modify the structure of the dog's legs or the actions of the joints in the future, changes will only be required in the respective classes.

Aggregation

Aggregation represents the concept where one class forms a part of or is a component of another class. This relationship is characterized by an "ownership" dynamic, where one object can own or contain other objects. Aggregation is typically employed to articulate the relationship between a whole and its parts, where the whole isn't responsible for the lifecycle of its parts. In an aggregation relationship, only the aggregate class is aware of the component class, but not vice versa. Components can be transferred from one aggregate to another without issues.

Aggregation resembles composition in that both can represent "parts" and "wholes", with "wholes" comprising one or several "parts". The key difference is whether the "whole" manages the lifecycle of the "parts" — i.e., their creation and destruction. For instance, a "tail" is part of a "dog"; when a dog object ceases to exist, there's no longer a need for the tail object. If the "dog" is responsible for creating and destroying the "tail", this is a composition. Conversely, consider "students" as part of a "classroom"; students may need to participate in activities beyond the classroom, indicating that the classroom shouldn't manage the lifecycle of "students". This relationship between students and classrooms is an example of aggregation, not composition.

........................

In the examples given, the Classroom class aggregates the Student class. The classroom maintains its students, but students can exist independently of the classroom. Aggregation allows for a clear hierarchical structure and whole-part relationships, facilitating the organization and management of system objects at a higher logical level.

Open/Closed Principle

The open/closed principle dictates that classes should be open for extension but closed for modification.

This means adding new functionalities should be possible without changing existing code. Modifications can introduce new bugs and lead to instability. Hence, code that functions correctly should remain unchanged as much as possible.

This principle concludes this section because it encapsulates the goal of integrating object-oriented programming into software development: to forge a system that is both flexible and stable. Flexibility allows for the addition of new functionalities without altering existing code. This principle is paramount, with prior methods and principles laying the foundation to achieve this objective. It applies not just to "classes" but to all software entities, including modules and functions, which should all be open for extension and closed to modification.

Using the StudentReport as an ongoing example:

........................

Afterward, we encounter a new requirement: report printing necessitates structured data, returned in a dictionary format. One might initially think to modify the program in the following manner:

........................

Such alterations breach the open/closed principle by continuously changing the StudentReport class to accommodate new report formats. So how can we introduce new functionalities without revising existing classes?

This necessitates abstract classes: introducing an abstract "Report Generator" class, with each report format represented as a specific class:

........................

Now, introducing a new report format merely involves adding a new concrete report generator class, bypassing the need to tweak any existing classes. Modified example code utilizing ReportGenerator:

........................

Thus, to generate reports in various formats, simply switch the generator associated with the UserReport instance. For instance:

........................

This approach strictly adheres to the open/closed principle since it doesn't require modifications to existing code to incorporate new functionalities.